Diagnosis of autism: Difference between revisions

from Autism spectrum split because very long |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 18:50, 10 June 2023

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: old sources, pre-DSM5. (March 2021) |

Autism spectrum disorder is a clinical diagnosis that is typically made by a physician based on reported and directly observed behavior in the affected individual.[1] According to the updated diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5-TR, in order to receive a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, one must present with "persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction" and "restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities."[2] These behaviors must begin in early childhood and affect one's ability to perform everyday tasks. Furthermore, the symptoms must not be fully explainable by intellectual developmental disorder or global developmental delay.

There are several factors that make autism spectrum disorder difficult to diagnose. First off, there are no standardized imaging, molecular or genetic tests that can be used to diagnose ASD.[3] Additionally, there is a lot of variety in how ASD affects individuals. The behavioral manifestations of ASD depend on one's developmental stage, age of presentation, current support, and individual variability.[4][2] Lastly, there are multiple conditions that may present similarly to autism spectrum disorder, including intellectual disability, hearing impairment, a specific language impairment[5] such as Landau–Kleffner syndrome.[6] ADHD, anxiety disorder, and psychotic disorders.[7] Furthermore, the presence of autism can make it harder to diagnose coexisting psychiatric disorders such as depression.[8]

Ideally the diagnosis of ASD should be given by a team of clinicians (e.g. pediatricians, child psychiatrists, child neurologists) based on information provided from the affected individual, caregivers, other medical professionals and from direct observation.[9] Evaluation of a child or adult for autism spectrum disorder typically starts with a pediatrician or primary care physician taking a developmental history and performing a physical exam. If warranted, the physician may refer the individual to an ASD specialist who will observe and assess cognitive, communication, family, and other factors using standardized tools, and taking into account any associated medical conditions.[5] A pediatric neuropsychologist is often asked to assess behavior and cognitive skills, both to aid diagnosis and to help recommend educational interventions.[10] Further workup may be performed after someone is diagnosed with ASD. This may include a clinical genetics evaluation particularly when other symptoms already suggest a genetic cause.[11] Although up to 40% of ASD cases may be linked to genetic causes,[12] it is not currently recommended to perform complete genetic testing on every individual who is diagnosed with ASD. Consensus guidelines for genetic testing in patients with ASD in the US and UK are limited to high-resolution chromosome and fragile X testing.[11] Metabolic and neuroimaging tests are also not routinely performed for diagnosis of ASD.[11]

The age at which ASD is diagnosed varies. Sometimes ASD can be diagnosed as early as 18 months, however, diagnosis of ASD before the age of two years may not be reliable.[3] Diagnosis becomes increasingly stable over the first three years of life. For example, a one-year-old who meets diagnostic criteria for ASD is less likely than a three-year-old to continue to do so a few years later.[13] Additionally, age of diagnosis may depend on the severity of ASD, with more severe forms of ASD more likely to be diagnosed at an earlier age.[14] Issues with access to healthcare such as cost of appointments or delays in making appointments often lead to delays in the diagnosis of ASD.[15] In the UK the National Autism Plan for Children recommends at most 30 weeks from first concern to completed diagnosis and assessment, though few cases are handled that quickly in practice.[5] Lack of access to appropriate medical care, broadening diagnostic criteria and increased awareness surrounding ASD in recent years has resulted in an increased number of individuals receiving a diagnosis of ASD as adults. Diagnosis of ASD in adults poses unique challenges because it still relies on an accurate developmental history and because autistic adults sometimes learn coping strategies, known as "masking" or "camouflaging", which may make it more difficult to obtain a diagnosis.[16][17][18]

The presentation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder may vary based on sex and gender identity. Most studies that have investigated the impact of gender on presentation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder have not differentiated between the impact of sex versus gender.[19] There is some evidence that autistic women and girls tend to show less repetitive behavior and may engage in more camouflaging than autistic males.[20] Camouflaging may include making oneself perform normative facial expressions and eye contact.[21] Differences in behavioral presentation and gender-stereotypes may make it more challenging to diagnose autism spectrum disorder in a timely manner in females.[19][20] A notable percentage of autistic females may be misdiagnosed, diagnosed after a considerable delay, or not diagnosed at all.[20]

Considering the unique challenges in diagnosing ASD using behavioral and observational assessment, specific US practice parameters for its assessment were published by the American Academy of Neurology in the year 2000,[22] the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in 1999,[4] and a consensus panel with representation from various professional societies in 1999.[23] The practice parameters outlined by these societies include an initial screening of children by general practitioners (i.e., "Level 1 screening") and for children who fail the initial screening, a comprehensive diagnostic assessment by experienced clinicians (i.e. "Level 2 evaluation"). Furthermore, it has been suggested that assessments of children with suspected ASD be evaluated within a developmental framework, include multiple informants (e.g., parents and teachers) from diverse contexts (e.g., home and school), and employ a multidisciplinary team of professionals (e.g., clinical psychologists, neuropsychologists, and psychiatrists).[24]

As of 2019[update], psychologists wait until a child showed initial evidence of ASD tendencies, then administer various psychological assessment tools to assess for ASD.[24] Among these measurements, the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) are considered the "gold standards" for assessing autistic children.[25][26] The ADI-R is a semi-structured parent interview that probes for symptoms of autism by evaluating a child's current behavior and developmental history. The ADOS is a semi-structured interactive evaluation of ASD symptoms that is used to measure social and communication abilities by eliciting several opportunities for spontaneous behaviors (e.g., eye contact) in standardized context. Various other questionnaires (e.g., The Childhood Autism Rating Scale, Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist) and tests of cognitive functioning (e.g., The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test) are typically included in an ASD assessment battery. The diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders (DISCO) may also be used.[27]

Screening

About half of parents of children with ASD notice their child's atypical behaviors by age 18 months, and about four-fifths notice by age 24 months.[13] If a child does not meet any of the following milestones, it "is an absolute indication to proceed with further evaluations. Delay in referral for such testing may delay early diagnosis and treatment and affect the [child's] long-term outcome."[23]

- No response to name (or gazing with direct eye contact) by 6 months.[28]

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word (spontaneous, not just echolalic) phrases by 24 months.

- Loss of any language or social skills, at any age.

The Japanese practice is to screen all children for ASD at 18 and 24 months, using autism-specific formal screening tests. In contrast, in the UK, children whose families or doctors recognize possible signs of autism are screened. It is not known which approach is more effective.[29][clarification needed] The UK National Screening Committee does not recommend universal ASD screening in young children. Their main concerns includes higher chances of misdiagnosis at younger ages and lack of evidence of effectiveness of early interventions.[30] There is no consensus between professional and expert bodies in the US on screening for autism in children younger than 3 years.[32]

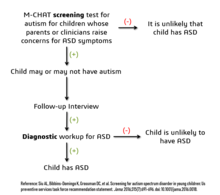

Screening tools include the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT), the Early Screening of Autistic Traits Questionnaire, and the First Year Inventory; initial data on M-CHAT and its predecessor, the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT), on children aged 18–30 months suggests that it is best used in a clinical setting and that it has low sensitivity (many false-negatives) but good specificity (few false-positives).[13] It may be more accurate to precede these tests with a broadband screener that does not distinguish ASD from other developmental disorders.[33] Screening tools designed for one culture's norms for behaviors like eye contact may be inappropriate for a different culture.[34] Although genetic screening for autism is generally still impractical, it can be considered in some cases, such as children with neurological symptoms and dysmorphic features.[35]

Misdiagnosis

There is a significant level of misdiagnosis of autism in neurodevelopmentally typical children; 18–37% of children diagnosed with ASD eventually lose their diagnosis. This high rate of lost diagnosis cannot be accounted for by successful ASD treatment alone. The most common reason parents reported as the cause of lost ASD diagnosis was new information about the child (73.5%), such as a replacement diagnosis. Other reasons included a diagnosis given so the child could receive ASD treatment (24.2%), ASD treatment success or maturation (21%), and parents disagreeing with the initial diagnosis (1.9%).[31][non-primary source needed]

Many of the children who were later found not to meet ASD diagnosis criteria then received diagnosis for another developmental disorder. Most common was ADHD, but other diagnoses included sensory disorders, anxiety, personality disorder, or learning disability.[31][non-primary source needed] Neurodevelopment and psychiatric disorders that are commonly misdiagnosed as ASD include specific language impairment, social communication disorder, anxiety disorder, reactive attachment disorder, cognitive impairment, visual impairment, hearing loss and normal behavioral variation.[36] Some behavioral variations that resemble autistic traits are repetitive behaviors, sensitivity to change in daily routines, focused interests, and toe-walking. These are considered normal behavioral variations when they do not cause impaired function. Boys are more likely to exhibit repetitive behaviors especially when excited, tired, bored, or stressed. Some ways of distinguishing typical behavioral variations from autistic behaviors are the ability of the child to suppress these behaviors and the absence of these behaviors during sleep.[9]

Comorbidity

ASDs tend to be highly comorbid with other disorders.[29] Comorbidity may increase with age and may worsen the course of youth with ASDs and make intervention and treatment more difficult. Distinguishing between ASDs and other diagnoses can be challenging because the traits of ASDs often overlap with symptoms of other disorders, and the characteristics of ASDs make traditional diagnostic procedures difficult.[37][38]

- The most common medical condition occurring in individuals with ASDs is seizure disorder or epilepsy, which occurs in 11–39% of autistic individuals.[39] The risk varies with age, cognitive level, and type of language disorder.[40]

- Tuberous sclerosis, an autosomal dominant genetic condition in which non-malignant tumors grow in the brain and on other vital organs, is present in 1–4% of individuals with ASDs.[41]

- Intellectual disabilities are some of the most common comorbid disorders with ASDs. As diagnosis is increasingly being given to people with higher functioning autism, there is a tendency for the proportion with comorbid intellectual disability to decrease over time. In a 2019 study, it was estimated that approximately 30-40% of people diagnosed with ASD also have intellectual disability.[42] Recent research has suggested that autistic people with intellectual disability tend to have rarer, more harmful, genetic mutations than those found in people solely diagnosed with autism.[43] A number of genetic syndromes causing intellectual disability may also be comorbid with ASD, including fragile X, Down, Prader-Willi, Angelman, Williams syndrome,[44] branched-chain keto acid dehydrogenase kinase deficiency,[45][46] and SYNGAP1-related intellectual disability.[47][48]

- Learning disabilities are also highly comorbid in individuals with an ASD. Approximately 25–75% of individuals with an ASD also have some degree of a learning disability.[49]

- Various anxiety disorders tend to co-occur with ASDs, with overall comorbidity rates of 7–84%.[50] They are common among children with ASD; there are no firm data, but studies have reported prevalences ranging from 11% to 84%. Many anxiety disorders have symptoms that are better explained by ASD itself, or are hard to distinguish from ASD's symptoms.[51]

- Rates of comorbid depression in individuals with an ASD range from 4–58%.[52]

- The relationship between ASD and schizophrenia remains a controversial subject under continued investigation, and recent meta-analyses have examined genetic, environmental, infectious, and immune risk factors that may be shared between the two conditions.[53][54][55] Oxidative stress, DNA damage and DNA repair have been postulated to play a role in the aetiopathology of both ASD and schizophrenia.[56]

- Deficits in ASD are often linked to behavior problems, such as difficulties following directions, being cooperative, and doing things on other people's terms.[57] Symptoms similar to those of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be part of an ASD diagnosis.[58]

- Sensory processing disorder is also comorbid with ASD, with comorbidity rates of 42–88%.[59]

- Starting in adolescence, some people with Asperger syndrome (26% in one sample)[60] fall under the criteria for the similar condition schizoid personality disorder, which is characterized by a lack of interest in social relationships, a tendency towards a solitary or sheltered lifestyle, secretiveness, emotional coldness, detachment and apathy.[60][61][62] Asperger syndrome was traditionally called "schizoid disorder of childhood."

- Genetic disorders - about 10–15% of autism cases have an identifiable Mendelian (single-gene) condition, chromosome abnormality, or other genetic syndromes.[63]

- Several metabolic defects, such as phenylketonuria, are associated with autistic symptoms.[64][verification needed]

- Gastrointestinal problems are one of the most commonly co-occurring medical conditions in autistic people.[65] These are linked to greater social impairment, irritability, language impairments, mood changes, and behavior and sleep problems.[65][66]

- Sleep problems affect about two-thirds of individuals with ASD at some point in childhood. These most commonly include symptoms of insomnia such as difficulty in falling asleep, frequent nocturnal awakenings, and early morning awakenings. Sleep problems are associated with difficult behaviors and family stress, and are often a focus of clinical attention over and above the primary ASD diagnosis.[67]

- ^ Baird G, Cass H, Slonims V (August 2003). "Diagnosis of autism". BMJ. 327 (7413): 488–493. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7413.488. PMC 188387. PMID 12946972.

- ^ a b "Section 2: Neurodevelopmental Disorders". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5-TR (Print) (Fifth edition, text revision. ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. 2022. ISBN 978-0-89042-575-6.

- ^ a b CDC (31 March 2022). "Screening and Diagnosis | Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | NCBDDD". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ a b Volkmar F, Cook EH, Pomeroy J, Realmuto G, Tanguay P (December 1999). "Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Working Group on Quality Issues". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 38 (12 Suppl): 32S–54S. doi:10.1016/s0890-8567(99)80003-3. PMID 10624084.

- ^ a b c Dover CJ, Le Couteur A (June 2007). "How to diagnose autism". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 92 (6): 540–545. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.086280. PMC 2066173. PMID 17515625.

- ^ Mantovani JF (May 2000). "Autistic regression and Landau-Kleffner syndrome: progress or confusion?". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 42 (5): 349–353. doi:10.1017/S0012162200210621. PMID 10855658.

- ^ Constantino JN, Charman T (March 2016). "Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: reconciling the syndrome, its diverse origins, and variation in expression" (PDF). The Lancet. Neurology. 15 (3): 279–91. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(15)00151-9. PMID 26497771. S2CID 206162618.

- ^ Matson JL, Neal D (2009). "Cormorbidity: diagnosing comorbid psychiatric conditions". Psychiatric Times. 26 (4). Archived from the original on 3 April 2013.

- ^ a b Simms MD (February 2017). "When Autistic Behavior Suggests a Disease Other than Classic Autism". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 64 (1): 127–138. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2016.08.009. PMID 27894440.

- ^ Kanne SM, Randolph JK, Farmer JE (December 2008). "Diagnostic and assessment findings: a bridge to academic planning for children with autism spectrum disorders". Neuropsychology Review. 18 (4): 367–384. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9072-z. PMID 18855144. S2CID 21108225.

- ^ a b c Caronna EB, Milunsky JM, Tager-Flusberg H (June 2008). "Autism spectrum disorders: clinical and research frontiers". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 93 (6): 518–523. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.115337. PMID 18305076. S2CID 18761374.

- ^ Schaefer GB, Mendelsohn NJ (January 2008). "Genetics evaluation for the etiologic diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders". Genetics in Medicine. 10 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815efdd7. PMID 18197051. S2CID 4468548.

- ^ a b c Landa RJ (March 2008). "Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in the first 3 years of life". Nature Clinical Practice. Neurology. 4 (3): 138–147. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0731. PMID 18253102.

- ^ Mandell DS, Novak MM, Zubritsky CD (December 2005). "Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders". Pediatrics. 116 (6): 1480–1486. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0185. PMC 2861294. PMID 16322174.

- ^ Shattuck PT, Grosse SD (2007). "Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders". Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 13 (2): 129–135. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20143. PMID 17563895.

- ^ Huang Y, Arnold SR, Foley KR, Trollor JN (August 2020). "Diagnosis of autism in adulthood: A scoping review". Autism. 24 (6): 1311–1327. doi:10.1177/1362361320903128. PMID 32106698. S2CID 211556350.

- ^ "Understanding Autism Masking and Its Consequences". Healthline. 2021-09-09. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ "6A02 Autism spectrum disorder". ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

Some individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder are capable of functioning adequately by making an exceptional effort to compensate for their symptoms during childhood, adolescence or adulthood. Such sustained effort, which may be more typical of affected females, can have a deleterious impact on mental health and well-being.

- ^ a b Lai MC, Szatmari P (March 2020). "Sex and gender impacts on the behavioural presentation and recognition of autism". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 33 (2): 117–123. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000575. PMID 31815760. S2CID 209164138.

- ^ a b c Lockwood Estrin G, Milner V, Spain D, Happé F, Colvert E (29 October 2020). "Barriers to Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis for Young Women and Girls: a Systematic Review". Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 8 (4). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 454–470. doi:10.1007/s40489-020-00225-8. PMC 8604819. PMID 34868805.

- ^ Hull L, Petrides KV, Allison C, Smith P, Baron-Cohen S, Lai MC, Mandy W (August 2017). ""Putting on My Best Normal": Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 47 (8): 2519–2534. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5. PMC 5509825. PMID 28527095.

- ^ Filipek PA, Accardo PJ, Ashwal S, Baranek GT, Cook EH, Dawson G, et al. (August 2000). "Practice parameter: screening and diagnosis of autism: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society". Neurology. 55 (4): 468–79. doi:10.1212/wnl.55.4.468. PMID 10953176.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Filipekwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Ozonoff S, Goodlin-Jones BL, Solomon M (September 2005). "Evidence-based assessment of autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 34 (3). Taylor & Francis: 523–40. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_8. ISSN 1537-4416. PMID 16083393. S2CID 14322690. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ Corsello C, Hus V, Pickles A, Risi S, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, Lord C (September 2007). "Between a ROC and a hard place: decision making and making decisions about using the SCQ". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 48 (9): 932–40. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01762.x. eISSN 1469-7610. hdl:2027.42/74877. ISSN 0021-9630. OCLC 01307942. PMID 17714378.

- ^ Huerta M, Lord C (February 2012). "Diagnostic evaluation of autism spectrum disorders". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 59 (1): 103–11, xi. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.10.018. PMC 3269006. PMID 22284796.

- ^ Kan CC, Buitelaar JK, van der Gaag RJ (June 2008). "Autismespectrumstoornissen bij volwassenen" [Autism spectrum disorders in adults]. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde (in Dutch). 152 (24): 1365–1369. PMID 18664213.

- ^ "Autism case training part 1: A closer look – key developmental milestones". CDC.gov. 18 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ a b Levy SE, Mandell DS, Schultz RT (November 2009). "Autism". Lancet. 374 (9701): 1627–1638. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61376-3. PMC 2863325. PMID 19819542. (Erratum: doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61666-8, [1])

- ^ a b c d e f Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, Ebell M, et al. (February 2016). "Screening for Autism Spectrum Disorder in Young Children: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 315 (7): 691–696. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.0018. PMID 26881372.

- ^ a b c Johnson CP, Myers SM (November 2007). "Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders". Pediatrics. 120 (5). American Academy of Pediatrics: 1183–1215. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2361. PMID 17967920. S2CID 218028., cited in Blumberg SJ, Zablotsky B, Avila RM, Colpe LJ, Pringle BA, Kogan MD (October 2016). "Diagnosis lost: Differences between children who had and who currently have an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis". Autism. 20 (7): 783–795. doi:10.1177/1362361315607724. PMC 4838550. PMID 26489772.

- ^ For example:

- US Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend universal screen of young children for autism due to poor evidence of benefits of this screening when parents and clinicians have no concerns about ASD. The major concern is a false-positive diagnosis that would burden a family with very time-consuming and financially demanding treatment interventions when it is not truly required. The Task Force also did not find any robust studies showing effectiveness of behavioral therapies in reducing ASD symptom severity.[30]

- American Academy of Pediatrics recommends ASD screening of all children between the ages if 18 and 24 months.[30] The AAP also recommends that children who screen positive for ASD be referred to treatment services without waiting for a comprehensive diagnostic workup[31]

- The American Academy of Family Physicians did not find sufficient evidence of benefit of universal early screening for ASD[30]

- The American Academy of Neurology and Child Neurology Society recommends general routine screening for delayed or abnormal development in children followed by screening for ASD only if indicated by the general developmental screening[30]

- The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommend routinely screening autism symptoms in young children[30]

- ^ Wetherby AM, Brosnan-Maddox S, Peace V, Newton L (September 2008). "Validation of the Infant-Toddler Checklist as a broadband screener for autism spectrum disorders from 9 to 24 months of age". Autism. 12 (5): 487–511. doi:10.1177/1362361308094501. PMC 2663025. PMID 18805944.

- ^ Wallis KE, Pinto-Martin J (May 2008). "The challenge of screening for autism spectrum disorder in a culturally diverse society". Acta Paediatrica. 97 (5): 539–540. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00720.x. PMID 18373717. S2CID 39744269.

- ^ Lintas C, Persico AM (January 2009). "Autistic phenotypes and genetic testing: state-of-the-art for the clinical geneticist". Journal of Medical Genetics. 46 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.2008.060871. PMC 2603481. PMID 18728070.

- ^ "Conditions That May Look Like Autism, but Aren't". WebMD. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Helverschou SB, Bakken TL, Martinsen H (2011). "Psychiatric Disorders in People with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Phenomenology and Recognition". In Matson JL, Sturmey P (eds.). International handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. New York: Springer. pp. 53–74. ISBN 9781441980649. OCLC 746203105.

- ^ Underwood L, McCarthy J, Tsakanikos E (September 2010). "Mental health of adults with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 23 (5): 421–6. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833cfc18. PMID 20613532. S2CID 13735841.

- ^ Ballaban-Gil K, Tuchman R (2000). "Epilepsy and epileptiform EEG: association with autism and language disorders". Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 6 (4): 300–8. doi:10.1002/1098-2779(2000)6:4<300::AID-MRDD9>3.0.CO;2-R. PMID 11107195.

- ^ Spence SJ, Schneider MT (June 2009). "The role of epilepsy and epileptiform EEGs in autism spectrum disorders". Pediatric Research. 65 (6): 599–606. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819e7168. PMC 2692092. PMID 19454962.

- ^ Wiznitzer M (September 2004). "Autism and tuberous sclerosis". Journal of Child Neurology. 19 (9): 675–9. doi:10.1177/08830738040190090701. PMID 15563013. S2CID 38157900.

- ^ Sala, G.; Hooley, M.; Attwood, T. (2019). "Autism and Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review of Sexuality and Relationship Education". Sexuality and Disability. 37 (3): 353–382. doi:10.1007/s11195-019-09577-4. S2CID 255011485.

- ^ Jensen, M.; Smolen, C.; Girirajan, S. (2020). "Gene discoveries in autism are biased towards comorbidity with intellectual disability". Journal of Medical Genetics. 57 (9): 647–652. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106476. PMC 7483239. PMID 32152248.

- ^ Zafeiriou DI, Ververi A, Vargiami E (June 2007). "Childhood autism and associated comorbidities". Brain & Development. 29 (5): 257–272. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2006.09.003. PMID 17084999. S2CID 16386209.

- ^ Schenkman, Lauren (2023-02-21). "Dietary changes ease traits in rare autism-linked condition". Spectrum | Autism Research News. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ Trine Tangeraas, Juliana R Constante, Paul Hoff Backe, Alfonso Oyarzábal, Julia Neugebauer, Natalie Weinhold, Francois Boemer, François G Debray, Burcu Ozturk-Hism, Gumus Evren, Eminoglu F Tuba, Oncul Ummuhan, Emma Footitt, James Davison, Caroline Martinez, Clarissa Bueno, Irene Machado, Pilar Rodríguez-Pombo, Nouriya Al-Sannaa, Mariela De Los Santos, Jordi Muchart López, Hatice Ozturkmen-Akay, Meryem Karaca, Mustafa Tekin, Sonia Pajares, Aida Ormazabal, Stephanie D Stoway, Rafael Artuch, Marjorie Dixon, Lars Mørkrid, Angeles García-Cazorla (2023-02-02). "BCKDK deficiency: a treatable neurodevelopmental disease amenable to newborn screening". Brain. doi:10.1093/brain/awad010. PMID 36729635. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Satterstrom FK, Kosmicki JA, Wang J, Breen MS, De Rubeis S, An JY, et al. (February 2020). "Large-Scale Exome Sequencing Study Implicates Both Developmental and Functional Changes in the Neurobiology of Autism". Cell. 180 (3): 568–584.e23. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.036. PMC 7250485. PMID 31981491.

- ^ Holder Jr JL, Hamdan FF, Michaud JL (2019). "SYNGAP1-Related Intellectual Disability". Gene Reviews (Review). PMID 30789692.

- ^ O'Brien G, Pearson J (June 2004). "Autism and learning disability". Autism. 8 (2): 125–40. doi:10.1177/1362361304042718. PMID 15165430. S2CID 17372893.

- ^ Mash EJ, Barkley RA (2003). Child Psychopathology. New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 409–454. ISBN 9781572306097.

- ^ White SW, Oswald D, Ollendick T, Scahill L (April 2009). "Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders". Clinical Psychology Review. 29 (3): 216–229. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.003. PMC 2692135. PMID 19223098.

- ^ Lainhart J (1999). "Psychiatric problems in individuals with autism, their parents and siblings". International Review of Psychiatry. 11 (4): 278–298. doi:10.1080/09540269974177.

- ^ Chisholm K, Lin A, Abu-Akel A, Wood SJ (August 2015). "The association between autism and schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A review of eight alternate models of co-occurrence" (PDF). Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 55: 173–83. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.012. PMID 25956249. S2CID 21450062.

- ^ Hamlyn J, Duhig M, McGrath J, Scott J (May 2013). "Modifiable risk factors for schizophrenia and autism—shared risk factors impacting on brain development". Neurobiology of Disease. 53: 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2012.10.023. PMID 23123588. S2CID 207067275.

- ^ Crespi BJ, Thiselton DL (October 2011). "Comparative immunogenetics of autism and schizophrenia". Genes, Brain and Behavior. 10 (7): 689–701. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00710.x. PMID 21649858. S2CID 851655.

- ^ Markkanen E, Meyer U, Dianov GL (June 2016). "DNA Damage and Repair in Schizophrenia and Autism: Implications for Cancer Comorbidity and Beyond". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 17 (6): 856. doi:10.3390/ijms17060856. PMC 4926390. PMID 27258260.

- ^ Tsakanikos E, Costello H, Holt G, Sturmey P, Bouras N (July 2007). "Behaviour management problems as predictors of psychotropic medication and use of psychiatric services in adults with autism" (PDF). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 37 (6): 1080–5. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0248-1. PMID 17053989. S2CID 14272598.

- ^ Rommelse NN, Franke B, Geurts HM, Hartman CA, Buitelaar JK (March 2010). "Shared heritability of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder". European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 19 (3): 281–95. doi:10.1007/s00787-010-0092-x. PMC 2839489. PMID 20148275.

- ^ Baranek GT (October 2002). "Efficacy of sensory and motor interventions for children with autism". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 32 (5): 397–422. doi:10.1023/A:1020541906063. PMID 12463517. S2CID 16449130.

- ^ a b Lugnegård T, Hallerbäck MU, Gillberg C (May 2012). "Personality disorders and autism spectrum disorders: what are the connections?". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 53 (4): 333–40. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.05.014. PMID 21821235.

- ^ Tantam D (December 1988). "Lifelong eccentricity and social isolation. II: Asperger's syndrome or schizoid personality disorder?". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 153: 783–91. doi:10.1192/bjp.153.6.783. PMID 3256377. S2CID 39433805.

- ^ Ekleberry SC (2008). "Cluster A - Schizoid Personality Disorder and Substance Use Disorders". Integrated Treatment for Co-Occurring Disorders: Personality Disorders and Addiction. Routledge. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0789036933.

- ^ Folstein SE, Rosen-Sheidley B (December 2001). "Genetics of autism: complex aetiology for a heterogeneous disorder". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 2 (12): 943–955. doi:10.1038/35103559. PMID 11733747. S2CID 9331084.

- ^ Manzi B, Loizzo AL, Giana G, Curatolo P (March 2008). "Autism and metabolic diseases". Journal of Child Neurology. 23 (3): 307–314. doi:10.1177/0883073807308698. PMID 18079313. S2CID 30809774.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

IsraelyanMargolis2018was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

WasilewskaKlukowski2015was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Richdale AL, Schreck KA (December 2009). "Sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, nature, & possible biopsychosocial aetiologies". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 13 (6): 403–411. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.02.003. PMID 19398354.