User:Chem4065sp13/sandbox

| This is a Wikipedia user page. This is not an encyclopedia article or the talk page for an encyclopedia article. If you find this page on any site other than Wikipedia, you are viewing a mirror site. Be aware that the page may be outdated and that the user in whose space this page is located may have no personal affiliation with any site other than Wikipedia. The original page is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User:Chem4065sp13/sandbox. |

Oral fluids, including saliva have been used to monitor hormones, drugs and other chemical substances for many years now. During the past decade, the use of oral fluids also has been advocated as a noninvasive alternative to the collection of blood for the detection of antibodies to a number of specific bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic agents[1]. Particular attention has been given to the value of oral fluids for the diagnosis of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[1]

Specimen Collection[edit]

Whole saliva, glandular-duct saliva, or mucosal transudates are specimens that can be collected for tests to detect HIV antibodies in oral secretions[1]. However, an understanding of the different fluids, as well as the proper way to collect fluid samples, is important for each specific test to obtain a proper analysis[1].

Whole saliva[edit]

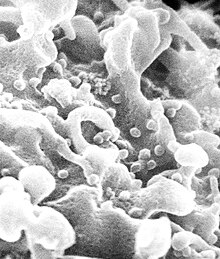

Whole salavia is the fluid obtained from the mouth and includes secretions from the parotid, submandibular, sublingual, and minor salivary glands as well as transudates of the oral mucosa[1]. It contains for the most part IgA and low levels of IgG[1]. Other materials, such as bacteria, leukocytes, mucin, epithelial cells, and food debris are also present in whole saliva which may break down IgG, which changes viscocity and makes the sample difficult to analyze[1]. There are two types of saliva that may be collected, unstimulated salavia and stimulus excreted salavia[1]. Unstimulated saliva is obtained by dripping saliva from lower lip into collection device. After 5 min, the subject spits any remaining saliva from the mouth[1]. To stimulate saliva and cause salivation, Parafilm, paraffin wax, neutral gum base, or rubber bands are suggested for use. Saliva can be stored 5 days at room temperature, for long term storage, 4 to −20°C is suggested[1]. Early work on detecting antibodies preferred the dripping method, however most of the samples received were of insufficient volume to run analyses and also suffered from possible contamination of the collection container[2].

Glandular-duct saliva[edit]

Saliva from the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands is collected by suction for the minor salivary glands[1]. Glandular-duct saliva largely secretes Ig and should be stored as recommended for whole saliva[1].

Oral mucosal transudates[edit]

Oral mucosal transudate is fluid from base between the teeth and gums, containing not only IgA but also IgG and IgM[1]. IgG and IgM are in the plasma but are found throughout the mouth via gingival crevices[1]. IgG concentration in oral mucosal transudates is less than concentrations in plasma and in higher concentrations than whole saliva samples[1]. Gingival crevicular fluid in the salavia is the most important thus far for detecting the plasma derived IgG and IgM antibodies[2]. Because of this, saliva shouldn't be stimulated for sample colletion to aid in keeping concentrations of anitbodies high so they may be detected[2]. “Crevicular fluid,” “gingival crevicular fluid,” and “crevicular fluid saliva” are also terms used for oral mucosal transudates[1].

Collection Devices[edit]

There are a variety of simple, safe and convenient devices commercially available for the collection of oral mucosal transudate specimens for the detection of HIV antibodies; including OraSure, Omni-SAL, Orapette, and Salivette[1]. Collection devices provided a sufficient specimen that is both homogeneous and low in viscosity, however, to ensure proper specimen collection, instructions must be carefully followed and specimen collection should be supervised[1].

Salivette[edit]

The Salivette device is as compressed cylinder with cotton that is gently chewed for a minute to release mucosal trasudates[1]. The cotton, now soaked with saliva, is placed in a tube with a small hole in its base. The smaller tube is placed in another larger tube where fluids are collected via centrifugation[1].

Orapette[edit]

A small rayon ball is placed into the mouth and fluid is collected around the teeth and gums until rayon ball is saturated[1]. The rayon ball is then placed into a receiving container, and the fluid is plunged out into a stoppered tube which is then suitable for transport and testing[1].

Omni-SAL[edit]

The Omni-SAL device has a compressed cotton pad on a plastic stem that is placed under the tongue on the floor of the mouth[1]. employs a compressed, absorbent cotton pad attached to a plastic stem[1]. The stem includes a color changing indicator showing when enough sample is present[1]. A transfer tube with 1.1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline at pH 7, inhibitors, surfactants, antimicrobial agents, and 0.2% sodium azide for preservation[1]. Once in the lab and ready for analysis, the fluid is collected from the pad and filtered with a piston style filter[1].

OraSure[edit]

The OraSure is a Food and Drug Adminstration (FDA) approved oral collection apparatus for use of detecting HIV antibodies[3]. A flat, cotton pad treated with salt solution (3.5% sodium chloride, 0.3% citric acid, 0.1% potassium sorbate, 0.1% sodium benzoate, and 0.1% gelatin) that is dried and attached to a plastic handle, is held in place in the lower cheek and gum for 2-5 minutes[3]. The collection device is then placed into a transport vial, containing 0.5% Tween 20 and 0.01% chlorhexidine digluconate. This vial is sent back to the OraSure company for analysis using centrifugation[3]. OraSure Technologies has developed a number of other HIV testing devices, such as OraQuick and OraQuick Advanced. OraQuick is an over the counter (OTC) test that produces results within 20 minutes[3].

Foam swab[edit]

A polystyrene foam swab developed at the Public Health Laboratory Service Virus Reference Division, London, United Kingdom, is another option for specimen collection[1]. The foam swab is rub along where the teeth and gums meet for one minute[1]. The fluids are then extracted from swab into a solution containing 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2, containing 0.2% Tween 20 and 10% fetal calf serum and centrifugated[1].

A sufficient volume of fluid must be obtained for testing with a typical yield from 0.5 to 1.5 ml of oral mucosal transudate[1]. There is no way to tell if the type of saliva and concentration of IgG (and other antibodies) has been obtained until analysis[1]. As more sensitive assays are developed, the concerns for concentrations and amounts of fluid necessary may change[1].

Laboratory Analysis[edit]

Outside of specific oral testing kits, other methods of analysis such as colorimetric/spectrophotometric, solid phase extraction and HPLC or CE with UV detection and immunoassays can be used in a laboratory setting when testing saliva[4]. Analyses are performed specifically looking for groups of molecules or as seen in this case, immunoglobulins[4]. Frequently, the use of commercial reagents are not suggested[4]. Procedures are modified for serum or plasma analysis and further modified for saliva[4]. In some cases, oral fluid analysis is preferred because of efficency over plasma analysis[4].

Advantages[edit]

In a direct head-to-head comparison of studies, both oral-based specimens and blood-based specimens show similar specificities. Oral-based specimens only showed a 2% lower pooled sensitivity than blood-based samples [5]. There are many other advantages to using oral fluids instead of serum or plasma collections, including the obtainment of samples without necessary training[1]. It also reduces the possibility of infection through blood exposure by eliminating the need for blood samples[1]. Eating in brevity to the test, tobacco use, oral hygiene, oral ulcers, or anticholinergic drugs do not effect the test [1]. The use of saliva and oral fluids broaden the screening programs, including use in dental offices, public health organizations, and community programs [1] Further, oral HIV testing provides sociological advantages. Among those who get tested using traditional methods, 31% of those who test positive do not return for their results [6]. These unsuccessful follow-ups are usually attributed to fear of a positive test, fear of disclosure, or belief that they are at low risk and will return a negative test. Oral HIV tests can deter these problems by allowing for quick responses and eliminating the need to return for results.[6]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak R. L. Hodinka; et al. (1998). Clin Vaccine Immunol. 5 no.4: 419–426.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c John V. Parry (2006). Annals of New York Academy of Science. 694 no.1: 216–233.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c d OraSure Technoligies. "OraSure".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e Silvia Chiappin; et al. (2007). Clinica Chimica Acta. 383: 30–40.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Nitika P. Pai; Bhairavi Balram; Sushmita Shivkumar; Jorge Luis Martinez-Cajas; Christiane Claessens; Gilles Lambert; Rosanna W Peeling; Lawrence Joseph; et al. (2012). "Head-to-head comparison of accuracy of a rapid point-of-care HIV test with oral versus whole-blood specimens: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lancet Infectious Diseases. 12 no.5: 373–380.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author1=(help) - ^ a b Steven Fine (2011). "Rapid Oral HIV Test".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)